The Human Spine: Structure, Function, and Clinical Relevance

Abstract

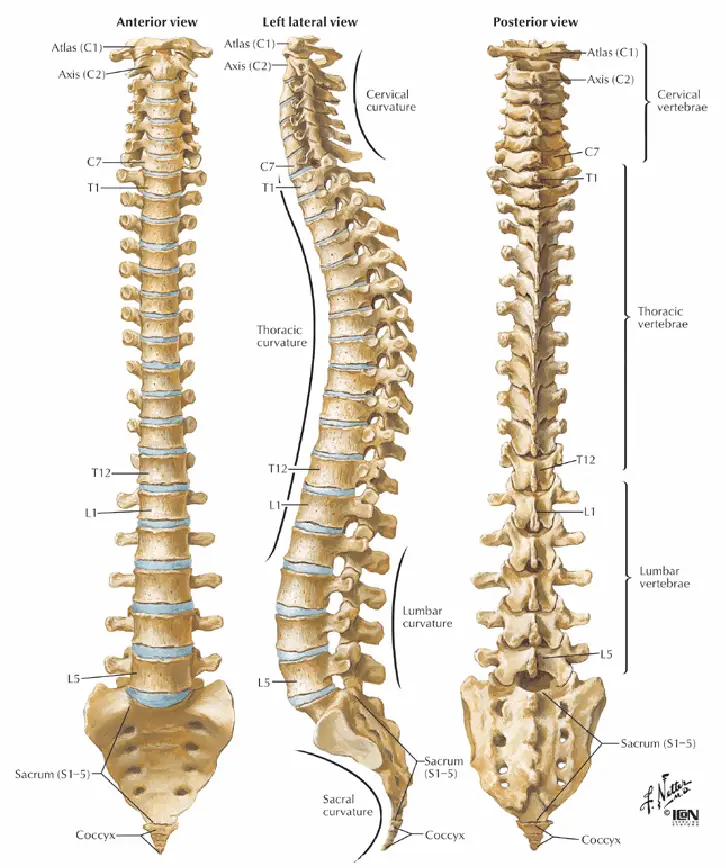

The human spine, also known as the vertebral column or backbone, is a central component of the axial skeleton. It provides structural support, protects the spinal cord, and enables a wide range of movements. Comprised of 33 vertebrae, the spine is divided into five regions: cervical, thoracic, lumbar, sacral, and coccygeal. This article explores the intricate anatomy, development, functions, and clinical significance of the human spine.

Introduction

The human spine is a complex and vital structure that serves multiple roles in the body. It acts as a pillar of support for the body’s weight, a protective encasement for the spinal cord, and a flexible framework that enables motion. The spine’s intricate anatomy and its critical functions make it a central focus in fields such as orthopedics, neurology, and physical therapy.

Anatomical Structure

The vertebral column consists of 33 vertebrae, which are categorized into five distinct regions:

- Cervical (7 vertebrae)

- Thoracic (12 vertebrae)

- Lumbar (5 vertebrae)

- Sacral (5 fused vertebrae)

- Coccygeal (4 fused vertebrae)

Each vertebra is a complex structure comprising several key components:

- Vertebral Body: The large, anterior portion that bears weight.

- Vertebral Arch: Formed by the pedicles and laminae, it encloses the spinal cord.

- Spinous Process: Projects posteriorly, providing attachment for muscles and ligaments.

- Transverse Processes: Extend laterally, serving as attachment points for muscles and ribs.

- Articular Processes: Facilitate articulation with adjacent vertebrae.

- Intervertebral Foramina: Openings for the passage of spinal nerves.

Cervical Region

The cervical spine (C1-C7) supports the skull and allows for a high degree of mobility. Unique features include:

- Atlas (C1): Supports the skull and allows for nodding motion.

- Axis (C2): Has a distinctive odontoid process (dens) that permits rotation.

Thoracic Region

The thoracic spine (T1-T12) is less mobile due to its connection with the rib cage, providing stability and protection for the thoracic organs.

Lumbar Region

The lumbar spine (L1-L5) bears the most weight and allows for significant motion, including flexion, extension, and rotation. The vertebrae are larger and more robust.

Sacral and Coccygeal Regions

The sacral spine (S1-S5) consists of fused vertebrae that form the sacrum, which articulates with the pelvis. The coccygeal region (Co1-Co4) consists of fused vertebrae that form the coccyx, or tailbone.

Development

The spine develops through a complex process of embryonic development:

- Notochord Formation: The notochord forms during early embryogenesis, serving as a precursor to the vertebral column.

- Somite Development: Paired blocks of mesoderm, called somites, differentiate into sclerotomes that give rise to the vertebrae.

- Chondrification and Ossification: Vertebrae begin as cartilaginous structures that gradually ossify through endochondral ossification.

Function

The spine serves several critical functions:

- Structural Support: Maintains upright posture and supports the weight of the head and trunk.

- Protection: Encloses and protects the spinal cord within the vertebral canal.

- Movement: Facilitates a range of motions, including flexion, extension, lateral bending, and rotation.

- Shock Absorption: Intervertebral discs act as cushions, absorbing shocks and reducing impact during movement.

Clinical Relevance

The spine’s complexity and central role in the body make it susceptible to various conditions and injuries:

- Degenerative Disc Disease: Age-related changes in intervertebral discs that can lead to pain and reduced mobility.

- Herniated Disc: Displacement of disc material that can compress spinal nerves, causing pain and neurological symptoms.

- Scoliosis: Abnormal lateral curvature of the spine that can affect posture and organ function.

- Spinal Stenosis: Narrowing of the spinal canal, which can compress the spinal cord and nerves, leading to pain and neurological deficits.

- Osteoporosis: Weakening of bones, increasing the risk of vertebral fractures.

- Spinal Cord Injury: Damage to the spinal cord that can result in loss of motor and sensory function below the level of injury.

Diagnostic and Therapeutic Approaches

Diagnosing spinal disorders often involves imaging techniques such as X-rays, MRI, and CT scans. Treatment varies based on the condition and may include:

- Physical Therapy: Exercises and techniques to improve strength, flexibility, and function.

- Medications: Pain relievers, anti-inflammatory drugs, and muscle relaxants.

- Surgical Interventions: Procedures such as discectomy, laminectomy, and spinal fusion to relieve pressure and stabilize the spine.

- Alternative Therapies: Approaches such as chiropractic care, acupuncture, and massage therapy.

Conclusion

The human spine is a remarkable and essential structure that plays a vital role in maintaining bodily function and overall health. Understanding its anatomy, development, and potential disorders is crucial for medical professionals and researchers. Ongoing advancements in medical science continue to enhance our ability to diagnose and treat spinal conditions, improving quality of life for patients.

References

- Standring, S. (2020). Gray’s Anatomy: The Anatomical Basis of Clinical Practice (42nd ed.). Elsevier.

- Moore, K. L., Dalley, A. F., & Agur, A. M. R. (2013). Clinically Oriented Anatomy (7th ed.). Lippincott Williams & Wilkins.

- Sadler, T. W. (2018). Langman’s Medical Embryology (14th ed.). Wolters Kluwer.

- White, A. A., & Panjabi, M. M. (1990). Clinical Biomechanics of the Spine (2nd ed.). Lippincott Williams & Wilkins.

- Nordin, M., & Frankel, V. H. (2001). Basic Biomechanics of the Musculoskeletal System (3rd ed.). Lippincott Williams & Wilkins.

This detailed exploration of the human spine underscores its complexity and critical importance, emphasizing the need for continued research and education in spinal health and disease management.

🎓 Want to become a certified instructor?

This lesson is part of our FREE Anatomy course. Create a free account to track your progress and earn your certificate!